The need for housing as a pathway to justice and safety

This section provides an overview of the breadth, depth and racial injustice of mass incarceration in terms of numbers, geography, and its impact on community safety. As such, it serves as an introduction to the nexus between mass incarceration and housing policy and practice. To combat prevalent fears and myths about people who have been involved in the criminal legal system, it also highlights facts and personal narratives that showcase how expanding housing access for people with convictions benefits all of us.

Scale and scope: Mass incarceration in the U.S.

As of 2023, there were nearly two million people incarcerated in the United States at the local, state, federal and tribal levels. This includes state and federal prisons, local jails, juvenile correctional facilities, immigration detention facilities, Indian country jails, military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.

Over 600,000 people are released from state and federal prisons, and over 10 million people are released from local jails every year. Not all of them go home – or even have a home to go to. For example, in New York City, nearly half of people released from state prisons are sent directly into the city shelter system.

Currently, there are approximately three million people on probation and parole who are subject to a wide range of mandates and conditions for which non-compliance can result in reentry. The mandates and conditions frequently include random drug tests, curfew, regular office visits, housing and employment requirements, the need to avoid arrest, and fines and fees. Technical violations can easily result in the revocation of community supervision, i.e., incarceration, with few due-process safeguards available as adults on probation and parole are only conditionally free in the community.

Rather than acting as an "alternative" to incarceration, community supervision frequently fuels mass incarceration. In 2021 alone, there were approximately 128,000 people incarcerated for these kinds of technical rules violations, accounting for 27% of all of the people admitted to state and federal prisons.

Even as the national prison population has declined, government spending on the carceral system rose 382% between 1980 and 2018. In 2015, the amount spent on jails and prisons in the U.S. reached $87 billion; we now spend more than twice as much on the carceral system as we do on cash welfare programs, which includes help with food, housing, home energy, childcare and job training.

That number is much higher when accounting for the social costs, which include lost wages, higher mortality rates of formerly incarcerated people and their infant children, evictions and relocations, diminished property values, and the increased likelihood of criminal legal system involvement for children who have incarcerated parents. Finally, mass incarceration exacerbates poverty and inequality, with research indicating that it has increased the poverty rate by ~20%.

There is a nexus between the sheer number of people in our prisons and jails nationally, and the ability of people leaving incarceration, and/or under supervision, to access stable housing. Offering greater access to the continuum of housing options, from emergency and transitional to permanent supportive and market rate private housing, on a hyper-local level, has broad impact and implications beyond the individual people and families housed.

People are better able to comply with conditions of supervision if they do not have to constantly worry about where they will sleep at night. The ability to comply is contingent upon multiple, interrelated factors, many of which have a financial component, and all of which are exacerbated by lack of stable housing. Housing instability also makes it harder to access services and programs.

People are more likely to be released to parole if they have a stable, verifiable address and, if needed, wraparound supports. One example of this is Richard. In New York, the Board of Parole finally agreed to release Richard after countless denials for parole and over 40 years in prison. His advocate is certain that he was finally granted release because he will immediately move into permanent, supportive housing specifically designed for recently incarcerated people who would otherwise be homeless.

The interplay between involvement in the criminal legal system and housing status is a challenge vast in its scope, but not, as will be described, without solutions that have the power to enhance the strength, well-being and safety of our communities.

1 Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2023, March 14). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html

2 Sawyer, W. (2022, August 25). Since you asked: How many people are released from state’s prisons and jails every year? Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/08/25/releasesbystate/

3 Simone, J. (2022). State of the Homeless 2022: New York at a Crossroads. Coalition for the Homeless. https://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/StateofThe-Homeless2022.pdf

4 Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2023, March 14). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html

5 Phelps, M. S., Dickens, H. N., & Beadle, T. (2023). Are Supervision Violations Filling Prisons? The Role of Probation, Parole, and New Offenses in Driving Mass Incarceration. Socius, 9 (January – December 2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221148631

6 Phelps, M. S., Dickens, H. N., & Beadle, T. (2023). Are Supervision Violations Filling Prisons? The Role of Probation, Parole, and New Offenses in Driving Mass Incarceration. Socius, 9 (January – December 2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221148631

7 Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2023, March 14). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html

8 Equal Justice Initiative. (n.d.). Criminal Justice Reform. https://eji.org/criminal-justice-reform/

9 Skaathun, B., Maviglia, F., Vo, A., McBride, A., Seymour, S., Mendez, S., Gonsalves, G., & Beletsky, L. (2022). Prioritization of carceral spending in U.S. cities: Development of the Carceral Resource Index (CRI) and the role of race and income inequality. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276818

10 Researchers at Washington University in St. Louis estimated that the additional social costs of incarceration cost the U.S. $1 trillion per year (i.e., nearly 6% of GDP). More information is available here: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2017/07/19/nine-lessons-about-criminal-justice-reform

11 Tanner, M.D. (2021, October 21). Poverty and Criminal Justice Reform. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/study/poverty-criminal-justice-reform

12Couloute, L. (2018, August). Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/housing.html

13Cleveland Neighborhood Progress (2019). Cuyahoga County Office of Reentry, Service and Asset Mapping Report at 13.

Race and gender disparities

The criminal legal system is rife with racial disparities and has a well-documented, deeply racialized history. Trends in prison population numbers and incarceration rates vary across states and, importantly, at an even more granular level that is deeply tied to issues of race across localities by zip code – even by block. Black and brown people have been and continue to be overrepresented in the prison population, even as it has declined in some areas. According to The Brennan Center for Justice, “… even at the current rate of decline, it will take decades to achieve incarceration rates appropriate to the current violent crime rate, which is roughly where it was in 1971. And while racial disparities are decreasing, the rate of incarceration for African Americans would only match whites after 100 years at the current pace.”

Black people comprise 13% of the overall population in the United States but account for 38% of the people in prison. In contrast, white people make up 38% of the prison population, yet account for 60% of the overall population in the United States.

Black men are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men, and Latinx men are 2.5 times more likely (Enterprise Community Partners, personal communication, 2021). In the United States, one in 81 Black adults is incarcerated in a state prison. Black and Latinx women also have higher rates of imprisonment than white women (1.6 and 1.3 times respectively).

13Alexander, M. (2010). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New Press.

14 Cullen, J. (2018, July 20). The History of Mass Incarceration. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/history-mass-incarceration

15 Sawyer, W. & Wagner, P. (2023, March 14). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2023. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2023.html

16 Nellis, A. (2021). The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in State Prisons. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/the-color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons-the-sentencing-project/

17 Monazzam, N. & Budd, K. M. (2023, April 3). Incarcerated Women and Girls. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/fact-sheet/incarcerated-women-and-girls/

Neighborhood impact

Enterprise’s Housing as a Pathway to Justice (H2J) national scan reveals that the systematic criminalization of Black, brown and low-income people is also reflected in spatial concentrations of incarceration at the local level. A variety of research projects have tracked these localized patterns of incarceration; many were spurred by findings from the Million Dollar Blocks project, which traced spending on incarceration to the neighborhood level. This project found that, in many of the biggest cities in the U.S., states spend more than $1 million a year to incarcerate residents of single city blocks.

-

In Detroit, a 2003 study found that 41% of incarcerated people from Wayne County, Michigan, returned to only eight zip codes in the city of Detroit. Most of those zip codes had experienced significant disinvestment and economic distress.

-

In Chicago, concentrations of high incarceration rates were found in the West Side and South Side – and these concentrations have held constant for more than two decades. In fact, there are blocks in Chicago’s West Side “… where nearly 70 percent of men between ages 18 and 54 are likely to have been subject to the criminal justice system.”

-

In Los Angeles, nearly half (46%) of the city residents arrested by the LAPD Metropolitan Division between 2012 and 2017 resided in just two city council districts. In 2019, a similar analysis revealed that L.A. County spent more than $2.5 million to incarcerate Black residents of five specific neighborhoods, including two neighborhoods where the county had spent at least $6.5 million per neighborhood.

-

Baltimore City residents comprise only 9% of the state population but account for 40% of the people incarcerated statewide. More than one-third of incarcerated people from the city hail from just 10 of the city’s 55 neighborhoods; this makes Baltimore City not only the city with the highest number of residents in state prison, but also the city with the densest concentration of people returning from incarceration.

-

In Washington, D.C., neighborhoods are sharply segregated by race. The majority of D.C. residents who are incarcerated come from three of the city’s wards, with two of those wards having the highest amount of housing assistance and instability. The population of those wards is over 90% Black/African American, although the overall city population is less than half that percentage.

These spatial patterns are both persistent and self-reinforcing over time. Research has shown that neighborhood rates of poverty, unemployment, family disruption and racial isolation are associated with higher levels of incarceration – and this relationship holds true even after accounting for actual crime rates experienced in a community. Growing up in a high-poverty or high-incarceration community (or both) increases a person’s exposure to crime and law enforcement. Clusters of vacant properties can facilitate increased criminal activity, or at a minimum, perceptions of increased crime. In addition, people who have been incarcerated and return to live in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty and transiency are more likely to recidivate.

Perceptions of danger, which are racialized and spatially concentrated in large part due to historic discriminatory policies, have evolved into implicit bias and racial stigma embedded in policy, thereby increasing punitive corrections practices including incarceration. These perceptions reinforce carceral policies and neighborhood segregation in parallel. To begin to address this persistent, self-reinforcing pattern we must start on the individual level by recognizing people’s humanity.

In an effort to assist our transition from prison to our communities as responsible citizens, and to create a more positive human image of ourselves, we are asking everyone to stop using these negative terms and to simply refer to us as PEOPLE. People currently or formerly incarcerated, PEOPLE on parole, PEOPLE recently released from prison, PEOPLE in prison, PEOPLE with criminal convictions, but PEOPLE ... It follows then, that calling me inmate, convict, prisoner, felon, or offender indicates a lack of understanding of who I am, but more importantly what I can be. I can be and am much more than an “ex-con,” or an “ex-offender,” or an “ex-felon” … We have made our mistakes, yes, but we have also paid or are paying our debts to society.

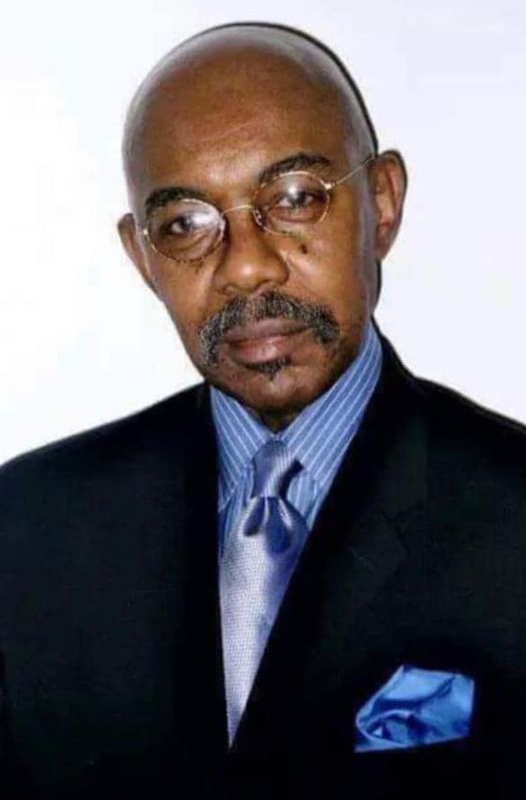

Eddie Ellis, founder, Center for NuLeadership on Urban Solutions

Incarceration is not only endemic to some big city neighborhoods, it also impacts rural and suburban counties of the U.S. In fact, incarceration rates are growing in rural counties while decreasing in larger counties, so much so that people in rural counties are about 50% more likely to be incarcerated than people in more populous counties.

This represents a shift from a decade ago when people in rural, suburban and urban areas were equally likely to go to prison. Some suspect this alteration is driven by policy shifts away from incarceration in larger cities, while the heroin epidemic and harsh sentencing practices may have driven the rise in incarceration in smaller counties.

Additionally, an Urban Institute analysis of myths surrounding the prison building boom found that in rural communities experiencing high rates of poverty, segregation, and where around half of the population is Black and Latinx, prisons fill an employment and economic stabilization gap, staving off the economic decline that occurred in similar areas. To curb the growth in the number of people incarcerated in these areas, it is critical for policymakers to address the economic conditions that made carceral facilities such an attractive option.

Even though the number of people incarcerated has declined, the United States still incarcerates more people than any other country, leading in both the number of people incarcerated and the prison population rate. The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) notes that, “… [d]espite making up close to 5% of the global population, the U.S. has nearly 25% of the world's prison population.”

Reentry

Hilton Webb, who earned an early discharge from parole in 2020, resided in supportive housing for formerly incarcerated people. He has made tremendous strides since his release in 2017, earning his Master of Social Work degree, passing the licensing exam and, despite his serious conviction, was granted a license in social work by the state of New York. Webb also found full-time employment in his chosen field. Yet, despite all of his achievements, finding permanent housing remains a challenge. He recalls the hardship he faced while in search of housing after being released. When told by a prospective landlord that he would be subject to a criminal background check, he said, “Well, I'll save you the time, you know, I've just gotten out of prison after 27 years.” The prospective landlord congratulated him, and then followed up with, “But you’re not going to be living here.” As Webb saw it, “Being honest was a detriment to me in finding housing.”(H. Webb, personal communication, February 27, 2023).

Research tells us that stable housing is one of the key components of recidivism prevention. A person's ability to find safe, secure and affordable housing after being released from prison or jail is essential to their effective reintegration into society. It provides a major stabilizing foundation and enhances public safety.

18 Kurgan, L., Cadora, E., Williams, S., Reinfurt, D., & Meisterlin, L. (n.d.). Million Dollar Blocks. Columbia University Center for Spatial Research. https://c4sr.columbia.edu/projects/million-dollar-blocks

19 Solomon, A., Thomson, G., & Keegan, S. (2004). Prisoner Reentry in Michigan. Urban Institute Justice Policy Center. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/prisoner-reentry-michigan

20 Cooper, D. & Lugalia-Hollon, R. (n.d.). Chicago’s Million Dollar Blocks. DataMade. https://chicagosmilliondollarblocks.com/#total

21 Bryan, I., Patlan, R., Dupuy, D., & Lytle Hernandez, K. (2019). The Los Angeles Police Department Metro Division. The Million Dollar Hoods Project. https://milliondollarhoods.pre.ss.ucla.edu/

22 Dupuy, D., Lee, E., Tso, M., & Lytle Hernández, K. (2020). Black People in the Los Angeles County Jail: Bookings by the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. The Million Dollar Hoods Project. https://milliondollarhoods.pre.ss.ucla.edu/

23 Enterprise Community Partners & Arcstratta. (n.d.). Housing as a Pathway to Justice: Landscape Analysis of Baltimore City. Enterprise Community Partners, Inc. https://www.enterprisecommunity.org/resources/housing-pathway-justice-landscape-analysis-baltimore-city

24 Enterprise Community Partners & Arcstratta. (n.d.). Housing as a Pathway to Justice: Landscape Analysis of The District of Columbia. Enterprise Community Partners, Inc. https://www.enterprisecommunity.org/resources/housing-pathway-justice-landscape-analysis-district-columbia

25 Sampson, R. J., & Loeffler, C. (2011). Punishment’s place: The local concentration of mass incarceration. Daedalus, 139(3), 20–31.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3043762/

26 Caloir, H., & Mangat, M. (2021, February 4). Can We Curb Crime by Cleaning the Corner? Shelterforce. https://shelterforce.org/2021/02/04/can-we-curb-crime-by-cleaning-the-corner/

27 Rhodes, W., Dyous, C., Kling, R., Hunt, D., & Luallen, J. (2013). Recidivism of Offenders on Federal Community Supervision. (Report no. 241018). National Criminal Justice Reference Service. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/bjs/grants/241018.pdf

28 Ghandnoosh, N. (2014, September 3). Race and Punishment: Racial Perceptions of Crime and Support for Punitive Policies. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/race-and-punishment-racial-perceptions-of-crime-and-support-for-punitive-policies/

29 Ellis, E. (n.d.), An Open Letter to Our Friends on the Question of Language. Center for NuLeadership on Human Justice & Healing. https://perma.cc/JQ67-UKHZ

30 Keller, J., & Pearce, A. (2016, September 2). A Small Indiana County Sends More People to Prison Than San Francisco and Durham, N.C., Combined. Why? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/02/upshot/new-geography-of-prisons.html

31 Keller, J., & Pearce, A. (2016, September 2). A Small Indiana County Sends More People to Prison Than San Francisco and Durham, N.C., Combined. Why? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/02/upshot/new-geography-of-prisons.html

32 Eason, J., & Nembhard, S. (2023, June 16). Debunking Four Myths About the Prison Building Boom Supporting Mass Incarceration. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/debunking-four-myths-about-prison-building-boom-supporting-mass-incarceration

33 Eason, J., & Nembhard, S. (2023, June 16). Debunking Four Myths About the Prison Building Boom Supporting Mass Incarceration. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/debunking-four-myths-about-prison-building-boom-supporting-mass-incarceration

34 Cullen, J. (2018, July 20). The History of Mass Incarceration. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/history-mass-incarceration

35 NAACP. (2022, November 4). Criminal Justice Fact Sheet. https://naacp.org/resources/criminal-justice-fact-sheet

36Jacobs, L. A., & Gottlieb, A. (2020). The Effect of Housing Circumstances on Recidivism: Evidence from a Sample of People on Probation in San Francisco. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(9), 1097–1115. DOI: 10.1177/0093854820942285

The need for housing as a pathway to justice

In 2022, Secretary Marcia L. Fudge of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development stated, “Too often, criminal histories are used to screen out or evict individuals who pose no actual threat to the health and safety of their neighbors. And this makes our communities less safe because providing returning citizens with housing helps them reintegrate and makes them less likely to reoffend.”

The housing narrative of people with conviction histories is often focused on the perceived public safety risks posed by the individuals reentering the community. Public perception needs to be reframed with an emphasis on the importance of housing in improving public safety. Fears and stereotypes about people who have convictions must be combatted with the facts. There is much evidence that demonstrates that an individual having a previous conviction is not a sole indicator of whether they will be a good tenant. As an example, a study of over 10,000 households showed that for those where at least one adult had a prior conviction, most of the conviction types accounted for had no statistically significant effect on housing outcomes.

Housing providers may fall prey to common misconceptions – often based on fear and implicit bias – about people with conviction histories. For example, research shows that people with murder convictions are among the least likely to be re-incarcerated for a serious crime. This is diametrically opposed to most people’s beliefs.

Even if people with conviction histories can afford rent, and otherwise meet all tenancy requirements, they often face discrimination on the basis of their conviction history alone. While having a blanket ban excluding all people with criminal convictions is illegal under the Fair Housing Act if it produces a discriminatory effect on the basis of race, the practice continues still today.

Criminal background checks are also extremely unreliable and very poorly regulated. Even people without convictions may face denials for faulty records, or suffer for being falsely connected to convictions that would not subject them to further scrutiny or denial under applicable laws.

In contrast, a landlord who participates in the Scatter-Site Housing Program with The Fortune Society, which provides apartments to tenants who have convictions, finds those tenants to be among their best. As one landlord said: “These individuals, they come in, they feel like they got a new lease on life. When they get a place, they cherish it, they take care of it, and they really become an example for the building. They become an example for all tenants.”

People with conviction histories make good neighbors. We are all better off when our fellow community members, especially those who are vulnerable to becoming homeless, have safe, stable housing. It is the foundation upon which all of us, and our families, build our lives, and therefore it is the foundation for safer, more diverse and equitable communities.

37 U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, Office of the Secretary. (2022, April 12). Eliminating Barriers That May Unnecessarily Prevent Individuals with Criminal Histories from Participating in HUD Programs. https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Main/documents/Memo_on_Criminal_Records.pdf

38 Warren, C. (2019, January). Success in Housing: How Much Does Criminal Background Matter? Amherst H. Wilder Foundation. https://www.wilder.org/wilder-research/research-library/success-housing-how-much-does-criminal-background-matter

39 Tuttle, S. & Rynell, A. (2019). Win-Win: Equipping Housing Providers to Open Doors to Housing for People with Criminal Records. Heartland Alliance. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/35116/35116.pdf

40U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development. (2016, April 4). Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate-Related Transactions. https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/HUD_OGCGUIDAPPFHASTANDCR.PDF

41 Lau, T. (2022, December 15). Fair Chance for Housing offers a fighting chance for New Yorkers with a conviction against racist rental practices. Amsterdam News. https://amsterdamnews.com/news/2022/12/15/fair-chance-for-housing-offers-fighting-chance-for-new-yorkers-with-a-conviction-against-racist-rental-practices/

42 Tuttle, S. & Rynell, A. (2019). Win-Win: Equipping Housing Providers to Open Doors to Housing for People with Criminal Records. Heartland Alliance. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/35116/35116.pdf

43 The Fortune Society. (2022, August 9). Why We Need Fair Chance for Housing for Justice Involved Individuals. Video. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFo8zkIwZfs